In the deeply personal series The dying man who would not die, photographer Sasha Mongin invites us into the intimate realm of her family history, closely intertwined with the contaminated blood scandal. With Brackish Tears, Santanu Dey presents an extended research project blending documentary and fiction, shedding light on the deep and lasting impact of the 1947 Partition of India on the Bengal region. In Wet Ground, Aria Shahrokhshahi explores Ukraine’s transformation amid the ongoing war, through photography, sculpture, and sound, revealing the persistent tension between everyday life and armed conflict.

Sasha Mongin

The dying man who would not die

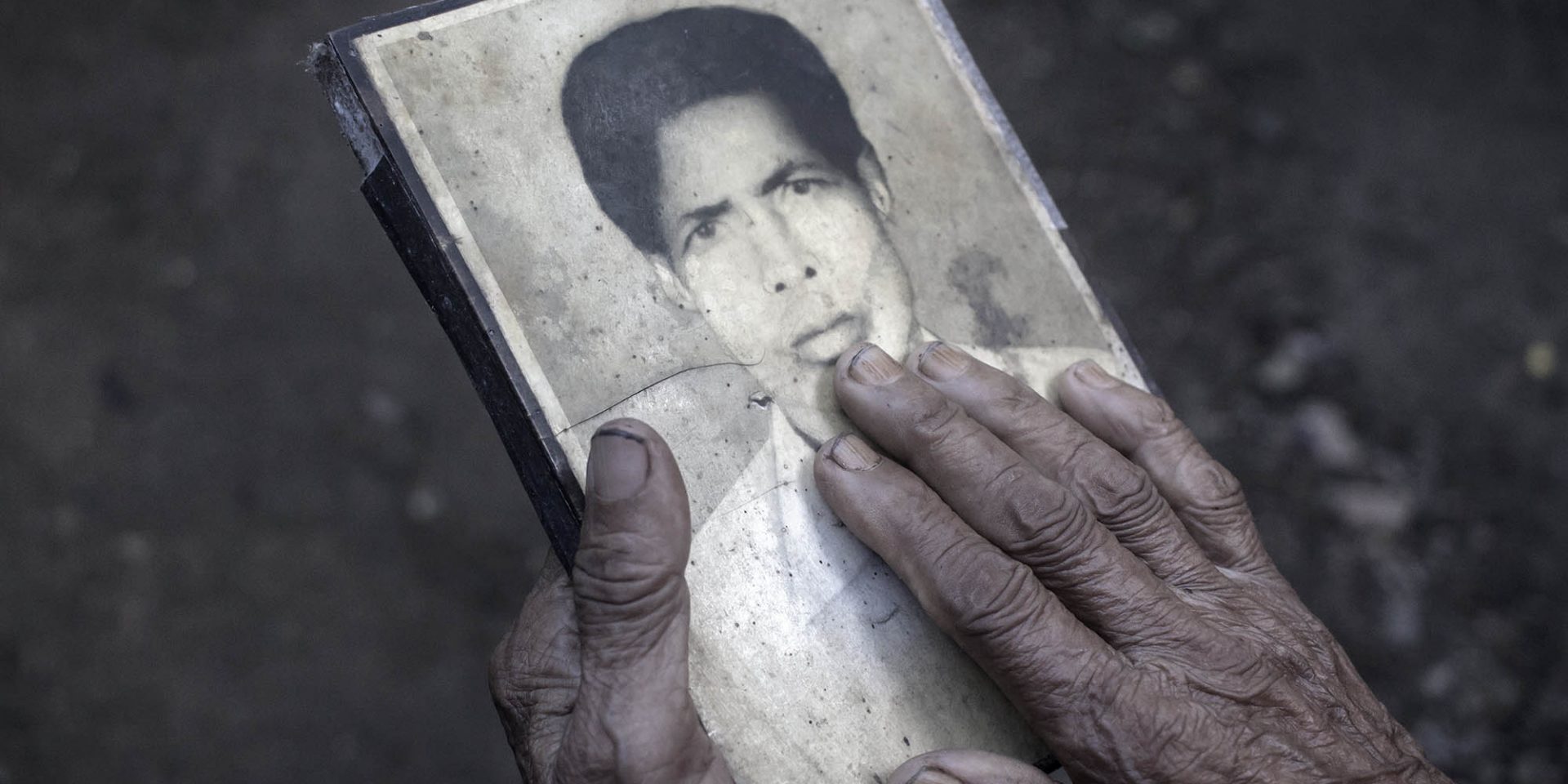

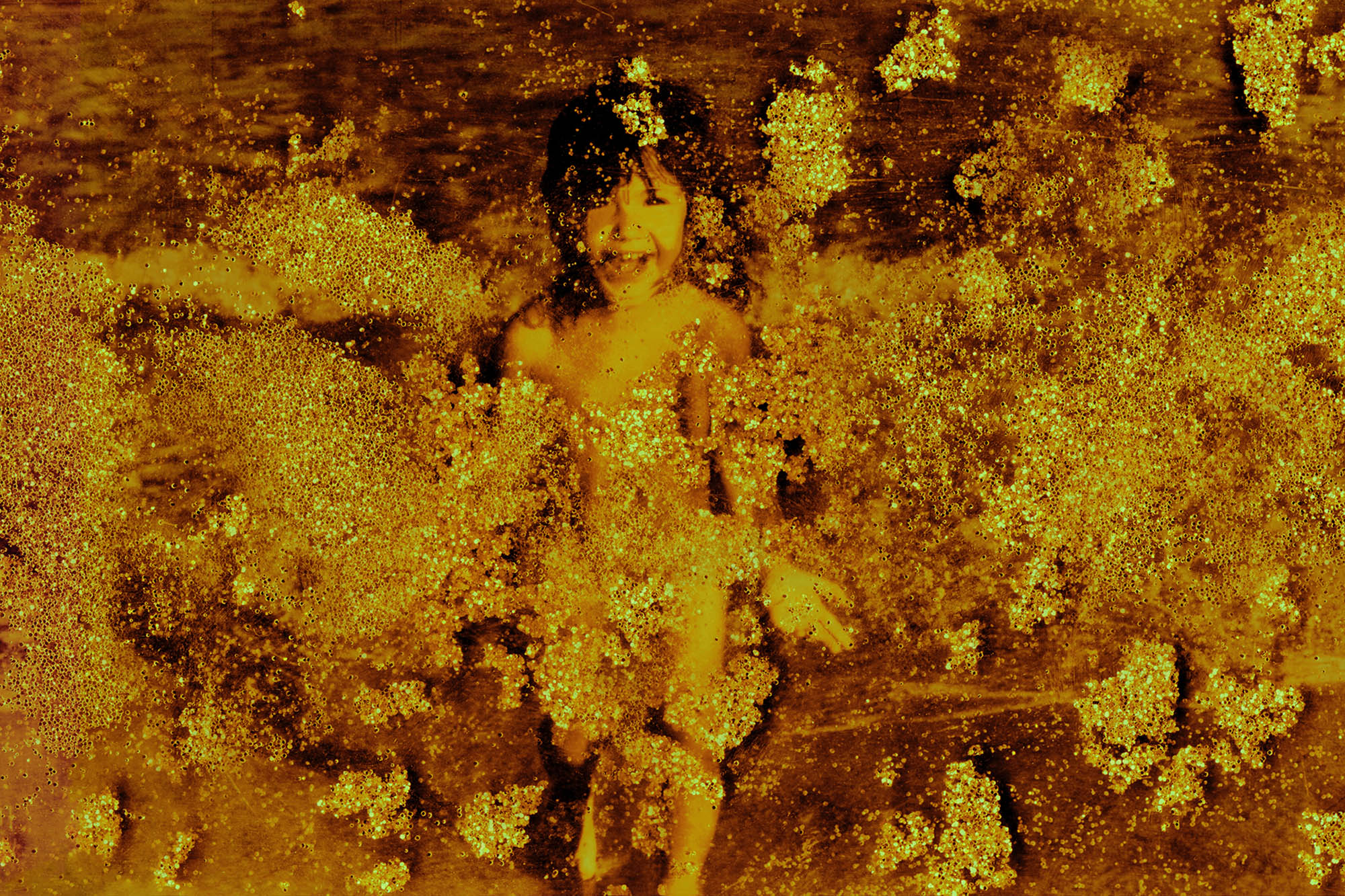

In a deeply personal series, photographer Sasha Mongin invites us into the intimate folds of her family history, which is closely intertwined with the contaminated blood scandal.

“My father contracted HIV during a blood transfusion in 1982, following heart surgery. AIDS allowed a rare virus to attack his brain, significantly impairing his motor skills and speech. I was seven years old at the time, and doctors gave him only a few months to live. But he proved them wrong—he’s still with us today.”

The images convey the perspective of a child who lived for years with the certainty that her father was going to die. Through her photographs, Sasha Mongin evokes her most vivid and haunting memories.While the subject is treated at times metaphorically and at others with stark clarity, all of the images are suffused with Sasha Mongin’s dreamlike and fantastical visual world.

“I remember denying my father’s illness, taking refuge in the fantasy that he was secretly going out at night. I remember my mother’s loneliness as friends and family gradually drifted away. I remember the strange relief of learning my father had AIDS and not a brain tumor, as I had been told until I was twelve. Death has always been a familiar presence in my life and in my parents’—they laugh about it, cry over it, and await it.”

Santanu Dey

Brackish Tears

With Brackish Tears, Santanu Dey presents a docu-ficational long-term research-based project that explores the profound aftermath of the ‘1947 Partition of India’ on Bengal-region. It examines how British colonialism deepened religious divisions to fracture the subcontinent, leaving lasting scars on unity. Through personal stories of displacement, this chapter unveils the enduring impact on lower-class refugees, their hierarchical oppression and cherished memories, revealing the complex legacy of colonialism, nationalism and communalism across generations.

“Millions of religious minorities migrated to India from East Pakistan after the Partition of 1947. While the upper caste and elites found new homes across India, the lower-caste refugees were exiled to inhospitable camps in Dandakaranya. In 1977, the Left Front party won the elections in West-Bengal with the promise to relocate the Namshudras (Lower-Caste) in Marichjhapi, an island in the Sundarban delta. Soon after, they reversed their promise and restricted the entries of the refugees to Bengal.

Thousands of refugees, nonetheless, defied the Government and moved to Marichjhapi. Within two years, they built embankments, roads, fisheries, a dispensary and a school. In response, the State Government surrounded the island with police boats to economically isolate them. On 13th May 1979, they burned the entire settlement, persecuted thousands of villagers and dumped their bodies in the Raimangal River. The actual casualty being unknown but surviving oral accounts claim that tigers in the area became habituated man-eaters after this genocide.

My work probes this massacre and traces the structure of violence linked with migration and resettlement back to the Mahabharata, an ancient Hindu epic. It has a distinct influence on the cultural imagination of the nation’s majoritarian religion. In the epic, the upper-caste Pandavas, aided by Lord Krishna and Fire god, burn the Khandava-forest, displacing indigenous Nagas and Mayas to build their kingdom’s capital, Indraprastha. As the rise of Hindu religious fanaticism and jingoism, this act reflects a troubling narrative of divine favouritism, where the gods’ unwavering support for the powerful underscores a stark contrast of subjugation and dominance.

Despite their contextual differences, these two events engage in a dialogue that reveals the systematic violence rooted in geopolitical contestations. The Marichjhapi massacre stands as a stark embodiment of deep-seated prejudices woven into hegemonic histories and mythological imagination. Through my photographs, I explore this asynchronous interplay, pairing archival fragments with mythological performance to expose the discursive frameworks that legitimize ethnic violence and superiority. As a visual archivist, I construct a multidimensional narrative of Marichjhapi—through portraits, belongings, landscapes, archives and oral testimonies—crafting a visual archive that brings forth the voices of the displaced and deepens our understanding of the global refugee crisis.”

Aria Shahrokhshahi

Wet Ground

Wet Ground explores Ukraine’s transformation amidst ongoing war, emphasising the dualities of violence and normalcy, destruction and resilience. Created from a place of compassion and commitment to social mobility, the work seeks to reveal what emerges from the ashes of conflict, placing the affected community at the centre of the narrative.

Initiated in 2019 and shaped through Aria Shahrokhshahi’s long-term engagement as a humanitarian volunteer with NGO Base UA, the project offers an embedded, collaborative perspective rooted in lived experience. Rejecting the conventional visual tropes of war photography, “Wet Ground” blends black-and-white documentary images with sculptures made from debris and clay sourced from bombed villages, and multimedia components including sound pieces generated using live minefield maps. These elements act as tactile embodiments of memory, creating a layered archive of resilience.

The work reclaims space for stories often overlooked in mainstream coverage and proposes an expanded role for documentary photography—one that engages ethically with trauma, legacy, and community. “Wet Ground” challenges dominant portrayals of conflict by highlighting how violence not only devastates landscapes but also fractures and transforms collective identity. It testifies to the persistence of life, culture, and imagination in the face of destruction.

The jury was composed of: Héloise Conésa (heritage curator at the BnF, in charge of the contemporary photography collection), Chloé Jafé (winner of the 2017 Bourse du Talent), Charlotte Flossaut (Founder and Artistic Director of Photo Doc), Aÿa de Faÿs (Photographie.com), Pierre Ciot (Deputy Secretary of the SAIF), Séverine Gay Degrendele (Curator of the Impulse Festival), Sylvaine Lecoeur (PixWays), Françoise Bornstein (Director of the Sit Down Gallery), and Chloé Tocabens (Head of Picto Foundation).